More than half the international students headed to undergraduate programs in Canada were turned away this year by immigration officials.

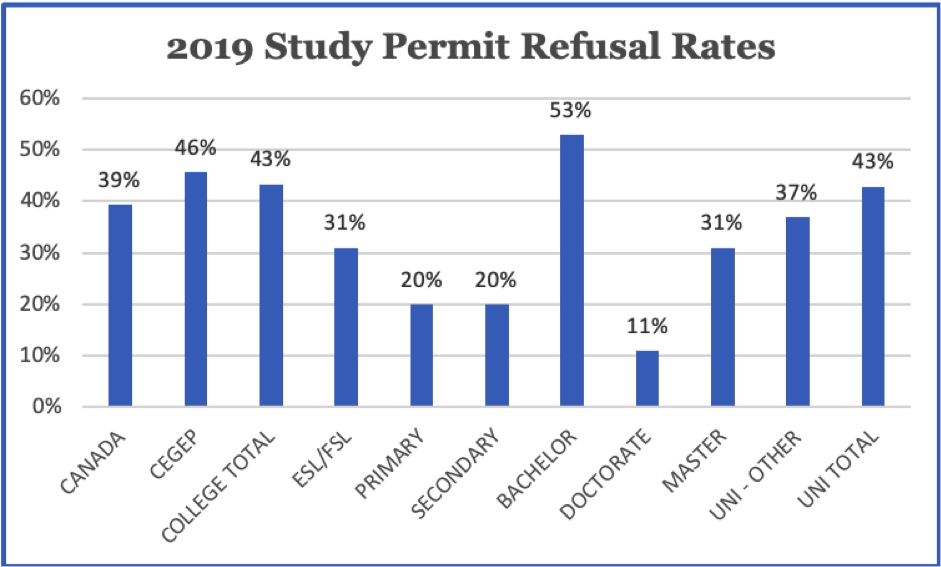

Between January and May, officers rejected 53 per cent of the study permit applications filed by foreign students hoping to begin a bachelor program in Canada, according to data provided by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada.

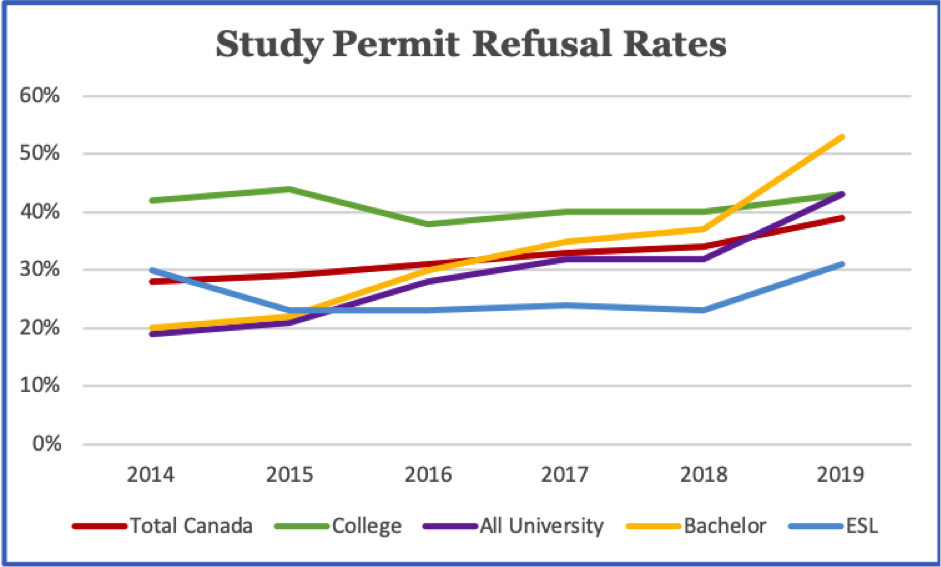

The record refusal rate is part of a trend that has seen immigration officials refuse a higher proportion of applications every year as international demand for Canadian education has soared. The overall refusal rate – including study permit applications to attend primary, secondary, post-secondary and language programs – was 39 per cent in the first five months of the year.

Reasons for refusal: fraud, danger, doubtful intentions

Twenty-eight per cent of all study permit applications were rejected by immigration officials in 2014. Four years later, in 2018, the overall rejection rate had climbed to 34 per cent. Demand for education boomed in that same period, with total applications almost doubling to more than 340,000 in 2018.

Robert Summerby-Murray is president of Saint Mary’s University, where 34 per cent of all students come from outside Canada. He is also chair of the Canadian Bureau for International Education, which promotes international education on behalf of more than 100 Canadian colleges, universities, schools and institutions.

He said study permit approvals have been improving for his students and he hasn’t heard of problems from other institutions.

“In some markets now, approvals are over 90 per cent,” he said of the experience of his own university this year. “We don’t see a 40 per cent refusal rate. That’s not our experience at all.”

Officials can refuse a study permit for many reasons: if they suspect the student may not return to their home country after graduation; if the student doesn’t have sufficient funds to pay for tuition and living costs while in Canada; if the student poses a health or security threat to Canada; if the officer doesn’t think the student’s academic plan makes sense; if the application is incomplete or inaccurate or if there is evidence of fraud in the application.

Harpreet Kochhar, assistant deputy minister of immigration, warned that fraud had become a significant problem in study permit applications. He told a conference of the Canadian Bureau of International Education that a sample audit found that 10% of the admission letters attached to study permit applications were false. In one case, he said, a supposed admission letter from Dalhousie University did not even spell the name of the university correctly.

Leave A Comment