We participated in the International Education Symposium SYMPLED2023 held 5 December 2023 in Sydney. Where international education in Australia was discussed at length. Pressure is mounting on the Australian government to curb net migration and international students.

Several speakers discussed the current situation in the international education market and the future steps for improvement and quality assurance. The Hon. Julian Hill MP gave very open and informative information on the government’s direction regarding international education in Australia. It was discussed that the social impact of international education is the main focus of the upcoming government initiatives.

Here are the highlights of incoming changes in early 2024:

- Students numbers caps – specifically for no PR leading courses such as Business, Management and so on

- An increase of student visa application fees up to $2500 per application

- Removal of compulsory six months of study in the main courses

- Removal of onshore commissions

- Possible regulation of agents in Australia or complete removal of agents

- PR outcome value for courses

- Increased taxation of international students

Student numbers

The number of international students in Australia was 645,516 as of August 2023 – roughly 6% higher than the March 2020 total of 611,077. This year, there were also 250,000 graduated students on post-study work visas and “pandemic” visas subclasses 485 and 408 (the sc 408 visa was scrapped from 1 September 2024.

There are several atypical factors influencing the volume of international students currently in Australia, which include:

- Students who were in Australia in the pandemic who extended their stay through temporary policies;

- Holders of sc408 COVID-pandemic visas extending to student visa;

- Students who, once borders reopened, came back to study in Australia as intended;

- New international students.

Cap on international students visa?

Shadow immigration minister Dan Tehan says the government has “no plan” for how to deal with the impact of record immigration, which he views as having a negative effect on Australian society: “The impact that it has on our transport infrastructure, the impact that it has on the environment, the impact that it has on housing, education, and news schools.”

Macroeconomist Gerard Minack concurs, saying that “a chronic lack of investment in the nation’s infrastructure relative to population growth has been massively detrimental to living standards.”

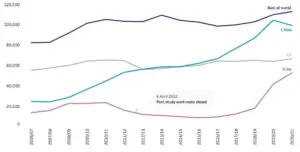

Another economist, Chris Richardson, argues that the quickest way to curb migration numbers would be to stem the flow of international students coming to Australia. He appeared on ABC’s QandA this month and said: “So we have now 725,000 students from the rest of the world studying in Australia — a year ago, that was 555,000. Yes, we sell education to the world and a lot of that we do well and some of it we don’t do as well, but it is a big part of the increase in the pressure at the moment and it is a relatively concentrated bit where we can make a change.”

But as Julie Hare and John Kehoe note in The Financial Review: “Migration experts say [capping international student numbers] could be counterproductive. A raft of changes already in place should reduce arrivals by curbing corrupt and exploitative behaviours among some education agents and private colleges, and improving the quality of student arriving.”

They quote Abul Rizvi, a former deputy secretary at the Immigration Department, who says: “These factors suggest we have reached peak migration” as “the co-called 408 COVID visas that 120,000 people are on expire over the next six to 12 months” and given that there has been an 80% decline in the number of state-issued skilled and regional visas for the financial year.”

Reserve Bank of Australia governor Michele Bullock also told The Financial Review that migration to Australia may be about to “settle down” because the pandemic-related factors that boosted international student numbers are easing: “We’ve got a situation where we’ve had to bring in all these students that we didn’t have for a few years, and none of them are leaving. Normally, they’d be turning over and they’re not. There’s some sense in which the immigration thing is going to settle down as we start to see the normal flows in and out of the student population.”

Should there be a special levy or tax for international students?

The idea of a tax was first proposed in the interim version of the “Australian Universities Accord” report. This report was commissioned by the Australian government and is due to be released in February 2024. It comprises a series of recommended policies for the health of the Australian higher education sector. The Hon Julian Hill MP attests that “an international student tax is a near certainty.”.

In summary, the report estimates that a tax on international students’ tuition fees could raise up to AUS$1 billion per year to help fund research and innovation in the university sector. But Tim Dodd, writing in The Australian, says that the tax proposal has taken on new meaning, with “the tax on international students being like a cake that gets bigger the more you eat of it.”

More ideas to get more money from the international students

Directors from the Australian policy think-tank the Grattan Institute, who firmly connect international student numbers to the housing crisis, have other recommendations for the government. In their dramatically titled opinion piece in The Sydney Morning Herald, “Immigration is smashing renters; it’s time to hike fees for international students,” the Institute’s Brendan Coates and Trent Wiltshire propose:

- Increasing student visa fees from AUS$710 to $2,500 to discourage students who would otherwise come to Australia for “cheaper, low-value courses.” They prefer this option to an international student tax and argue that it “would raise some $1 billion a year which could fund support for vulnerable renters.”

- Raising minimum English scores for incoming students, “keep cracking down on the dodgy providers of low-value courses, and limit visa jumping by students already in Australia by applying a new Genuine Student Test as recommended in the Parkinson review of the migration system.”

- “Making it less attractive for struggling students to stay in Australia after they graduate, by offering them shorter post-study work visas. Visa extensions for graduates with degrees in nominated areas of shortage, and for living in the regions, should be scrapped, and visa extensions only offered to those earning at least $70,000 a year. These changes would result in about 140,000 fewer international students and graduates in Australia by 2030 than under current policy.”

- “Abolishing rules that allow [working holidaymakers] to extend their stay if they work in regional areas” and limiting their visa to one year.”

What are the other countries doing about international students?

The current situation bears a strong resemblance to the 2010s in the UK, when anti-immigrant sentiment was rising. In 2014, then-Home Secretary Theresa May restricted post-study work rights for international students in an effort to curb net migration. The Migration Observatory reports that “Work visa grants to non-EU former students fell by 84% from 2011 to 2020, before the decision to re-introduce post-study work rights in 2021.”

The Observatory has a telling graphic illustrating the correlation between Ms May’s restriction of work rights and Indian student numbers in UK over time.

New international students in UK universities 2006/07 to 2020/21. Source: The Migration Observatory

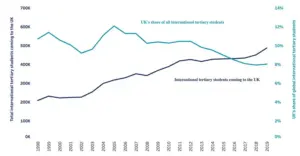

The Observatory has another fascinating graphic showing the correlation between the years in which Ms May restricted international student work rights and the years in which the UK began losing market share of global tertiary students (to Australia, Canada, and China).

The UK’s share of global tertiary students 1998-2019. Source: The Migration Observatory

International students, despite their massive contribution to the economies of the countries in which they study, are commonly the most affected when governments attempt to curb migration. As the Migration Observatory observes in its analysis of likely migration flows to the UK to 2030:

“Of the categories in our model, work and study are the ones that are most amenable to policy changes. Policymakers interested in shaping net migration levels in either direction are thus likely to find more impact in these categories. Indeed, work-visa policy is likely to be the main factor affecting the contribution of both work and study to long-term net migration, since students usually need to switch to work visas in order to remain in the UK permanently.”

International education is Australia’s largest service export, and the contribution international students made to the economy through direct spending on tuition and living expenses that benefits multiple sectors outside of education amounted to AUS$29 billion in 2022. This contribution can only have risen in 2023 given that the number of students is now higher than in 2019, a year, incidentally, when the economic impact of international students in Australia was AUS$40 billion.

It didn’t take long for the Australian government to mess up international education again

The international student numbers increased once Australia’s border reopened to allow people back into the country in December 2021. The number of foreign students holding Australian student visas now exceeds the pre-COVID numbers. The surge of foreign students in Australia is becoming a lightning rod for politicians courting voters who want to see immigration levels lowered in the ntext of skyrocketing rental fees and house prices. Australia’s international education sector is bracing for Home Affairs Minister Clare O’Neil’s much-anticipated migration review, expected to be released in December.

These dynamics are unusual, and their cumulative effect will weaken international education in Australia for a number of reasons. It is looking ever-more likely that there will be a new raft of policies that could affect the following for international students interested in studying in Australia:

- The price of education;

- The cost of applying to Australian schools and universities;

- Post-study work rights;

- Increased visa fees;

- Caps on students visas

- Higher taxation of international students;

Clearly, much is at stake for Australia’s international education sector. We can only hope that the industry will be invited to the discussions and challenge the government strategies that will have a negative impact on international education in Australia.

Sources:

Leave A Comment